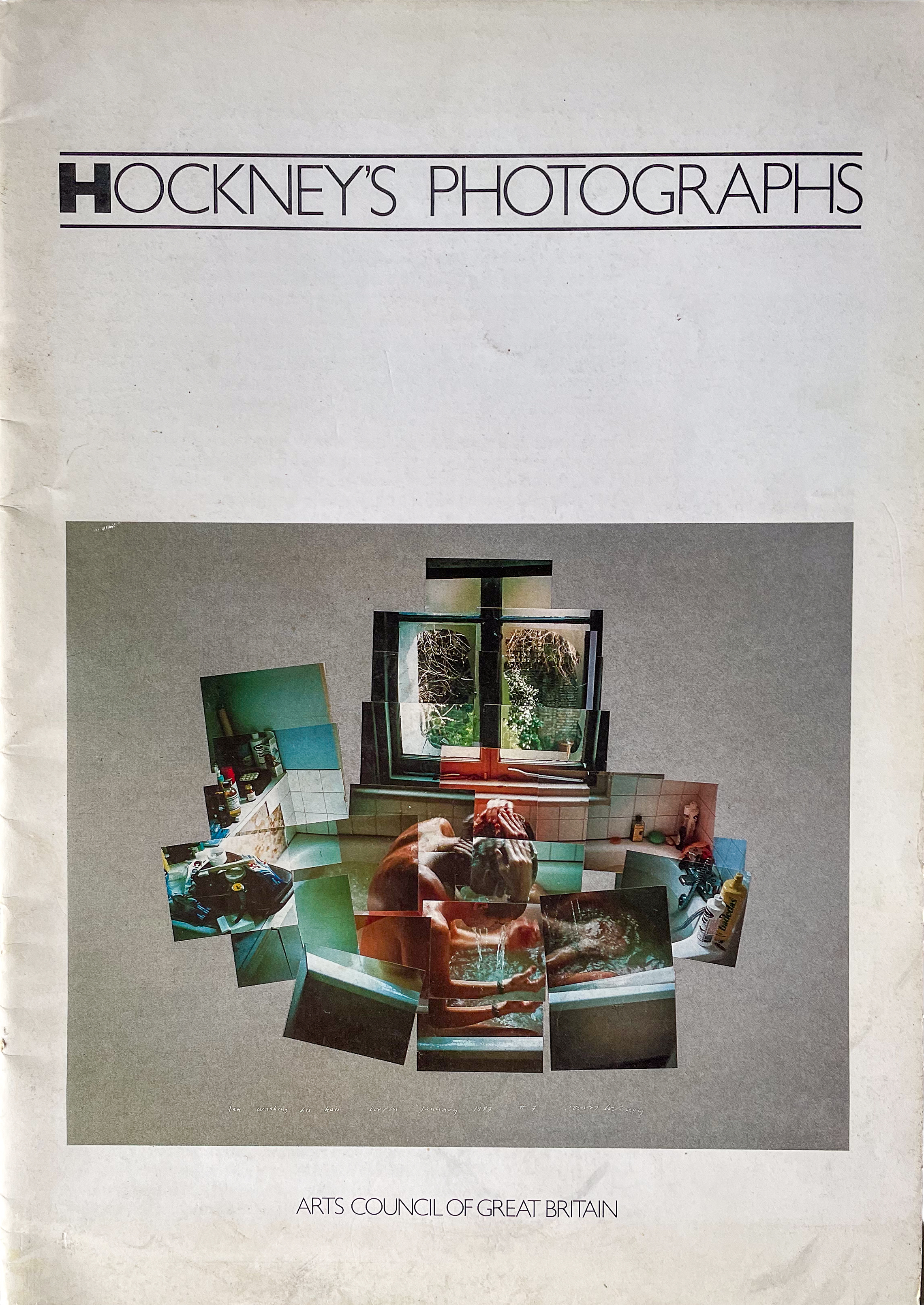

A new way of seeing

This well-worn catalogue of Hockney’s Photographs is one of the best things I spent my money on as a teenager. I purchased it at the first exhibition I went to independently (at the much missed Royal Photographic Society on Milsom Street in Bath).

I was a callow 16 year old, in the summer after my ‘O’ Levels, on holiday in Bath with my best friend.

It was one of the most formative weeks of my life. Not only was this my first photo exhibition, but also the first time I walked round Bristol and Bath. I was so drawn to the area that two years later I went to university in Bristol and have lived in and around Bath for all but four years since I graduated.

Now, each time I see one of David Hockney’s Polaroids or ‘Joiners’ I recall how a switch in my brain flicked on all those years ago. Here was a new way of seeing I had never noticed before. A point of view which was so original to my young eyes. Photography could be so much more than a snapshot.

Sun on the pool, Los Angeles. 13th April 1982.

“I mean, photography is all right if you don’t mind looking at the world from the point of view of a paralysed Cyclops - for a split second. But that’s not what it’s like to live in the world.”

This is the challenge which confronted David Hockney in the early 80s. He felt photography excluded more than it revealed. That a single click of the shutter was an unnatural, one dimensional way of seeing.

He called his Polaroids “drawing with the camera.” They offered multiple viewpoints mimicing the fluctuating glances that make up vision. Similar in concept to Cubist art.

What could have been one click of a shutter is broken down into hundreds of micro-scenes. Each with a slightly different perspective, or light. The white borders of the Polaroid, and the edges of the 35mm print, delineate a small portion of the scene and encourages you to look at each one individually. Every frame is a millisecond which combines to add layers of time to the whole collage in a way a single frame cannot.

“A photograph cannot really have layers of time in the way a painting can.”

You feel as though you are there, standing beside him. It feels like it’s the closest you’ll get to mimicking how you really see.

The every day

The scenes he chooses reflect his day to day living. The inside of a hotel room, watching Gregory swim, a car steering wheel, spending time with friends.

Hockney used an every day compact camera (firstly a Polaroid SX70 and then a Pentax 110) and a high street chemist to process the films.

Everyday tools are enough to change how we see. You don’t need expensive toys to explore your creativity and be original.

His works in his own words.

Walking in the Zen Garden

“They said perspective was built into the camera. But my experiments showed that when you put two or three photographs together, you can alter perspective. The first picture I made where I felt I had done that was in Japan where I photographed Walking in the Zen Garden at the Ryoanji Temple, Kyoto, Feb. 1983. I made it into a rectangle by moving around myself and taking shots from different positions, whereas any other photograph would show it as a triangle.... I was very excited when I did that. I felt I made a photograph without Western perspective.”

Pearblossom Hwy 11-18 April 1986

This composite took him a week to shoot. He used hundreds of photos. The frame in the centre is the one conventional picture - the highway disappears into the distance.

“It is the only picture that attempts to depict space, every other picture is about a surface-road signs, the road itself, shrubs, Joshua trees, and garbage at the side of the road.”

The Grand Canyon Looking North, September 1982

“I’ve always loved the wide-open spaces of the American West. But I was never able to capture them in photography, to convey the sense of what it's actually like to be there, facing that expanse-that incredible sense of spaciousness, which is somehow as elusive to ordinary photography as time is.”